The Uncanny Valley of Marketing Automation

Raise your hand if you have been on the other end of a phone call with an AI just saying “speak to someone,” over and over trying to get a real person.

Or maybe you got in an argument with an online chat bot because its skip logic was flawed, or the faux cheerfulness rubbed you the wrong way?

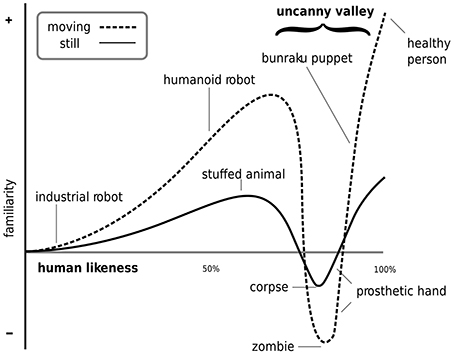

Reactions like these resemble an online cousin to the “Uncanny Valley” phenomenon.

First coined by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970, the phrase “Uncanny Valley” refers to the relationship between a robot’s lifelike appeal and the unsettled emotional response it elicits when the robot tries to mimic a realistic human, but falls short. The theory is that people are more comfortable with automation that attempts little to no human likeness, but comfort level drops once the effort to imbue human characteristics into an AI or bot is judged and falls short. Interactions that are close-but-not-quite-lifelike (E.g. prosthetics, mannequins, or avatars) raise expectations for our brain, and when those expectations are not met, our brains switch to ‘not OK’ - it feels somehow off, alienating… uncanny.

So what problems does this cause for marketing automation? How does the uncanny valley influence a customer’s emotional empathy during a marketing interaction? When is automation likely to be successful?

For direction we can look again to Masahiro Mori, who, in a 2011 interview in Wired argued that there are times when it’s better to design tools that stop well short of the point of uncanniness. Sometimes the goal is not to keep the interaction as human as possible, but to exchange information and value efficiently.

Companies should consider four factors when designing their marketing automation: the personality of the automation, analysis of the audience, the value and speed of the exchange, and conversational layers.

Research has shown that the personality of the automation should adapt to the job rather than the user’s personality. For jobs that entail evaluation, judgment, diplomacy, or artistic creation, people prefer a human to perform the job. On the other hand, when the task involves data retrieval or acquisition, or service to others, people tend to be comfortable with “robots” doing the job.

Remember to match your tactics to your intended target because on the other side of your well-intentioned marketing interactions is an actual person with questions, needs, and life experiences that may be different from the designer’s. A visitor’s age, culture, situation, and pre-existing attitudes will influence their emotional response to AI and automation.

Think thoroughly about your audience and how the principles about what makes a robot acceptable apply to their specific circumstances. Consider the value exchange: what are you offering to earn their information and trust? Some customers would rather an automation simply ask for the information it needs and complete the task without the frills of an avatar that displays all the friendly humanity of a bad salesman. (For this reason alone, it’s essential to always have a transition to a real human readily available.)

When balancing the demands of standardization, personalization, and humanization, remember that natural conversations tend to occur in layers, starting broadly and then becoming more detailed and personalized as each party learns more detail. Asking customers to share too much too soon can feel intrusive, while taking too long grows stale and invites churn.

Apply these principles and design your engagements in a way that is relevant and valuable to both parties. The result will feel more authentic and better track with the comfort level of each visitor.

.png)